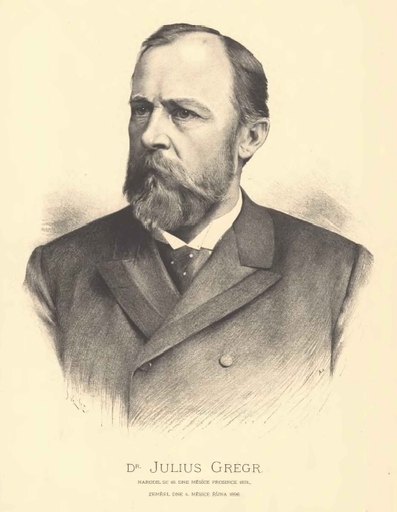

Czech lawyer and solicitor, a leading journalist and politician, cofounder of the so-called Young Czech Party and the Národní listy newspapers. He was one of the first Czech politicians to rely on newspapers in forming the public opinion.

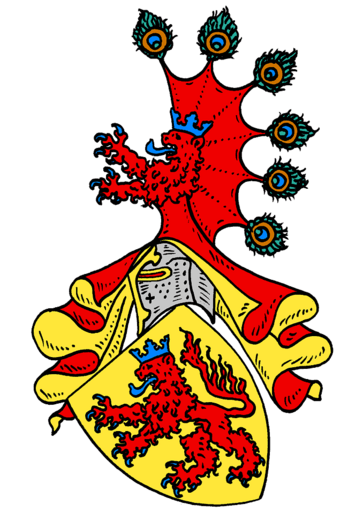

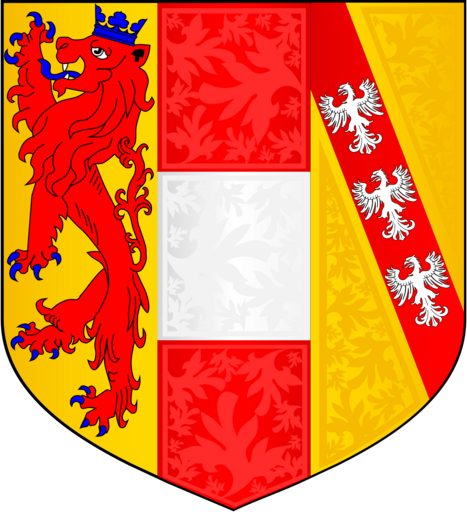

Prominent royal dynasty whose members fundamentally influenced the history of Central Europe, including the Czech lands, from the 13th to the 18th centuries. They ruled Bohemia in 1306–1307, 1437–1457 and 1526–1740.

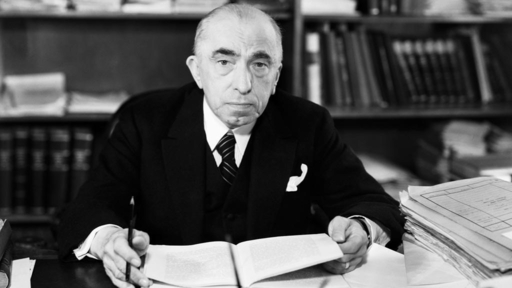

Czech lawyer and statesman, President of the Supreme Administration Court of Czechoslovakia, President of the Czechoslovak Republic and State President of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia.

The most famous historical humanities work, published in 1541. The Chronicle’s popularity was mostly due to its use of Czech language close to common speech.

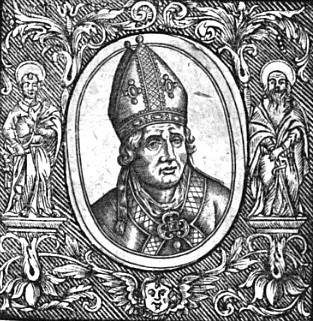

Duke of Bohemia between 1193 and 1197, the only ruler in Czech history to simultaneously hold the function of the bishop of Prague. He was a very ambitious, although unscrupulous politician and a capable conspirator.

Count of Tyrol and Duke of Carinthia between 1295 and 1335, King of Bohemia in 1306 and between 1307 and 1310. The first ruler of Bohemia who was not a member of the Přemyslid dynasty.

Acting Reich-Protector of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia during the Second World War. He was the most notorious and hated Nazi in Czechoslovakia.

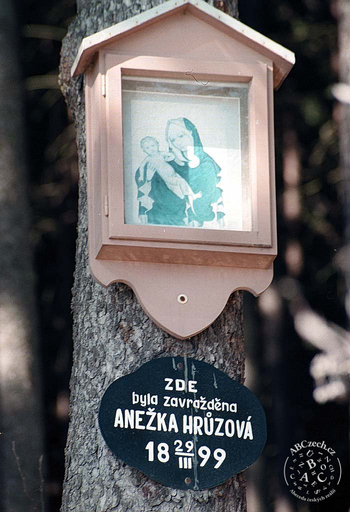

Process involving Leopold Hilsner, a young Jew unjustly accused of a murder of a young Christian girl. It was the largest expression of antisemitism in the Czech lands in the 19th century and, in a way, the Czech version of the well-known Dreyfus Affair.

Czechoslovak politician, statesman and journalist originally from Slovakia, the tenth president of the government of the Czechoslovak Republic.

Czech physician, ethnographer and explorer, who went on two expeditions to Africa and created a large natural-scientific and ethnographic collection.

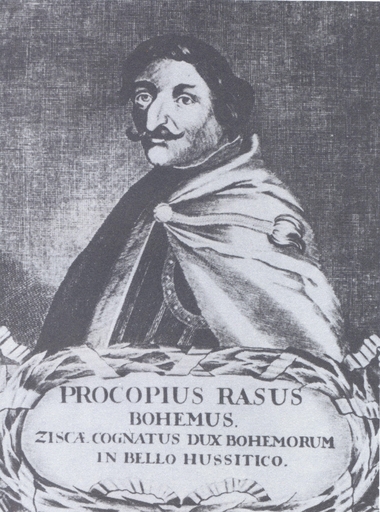

Prominent Hussite politician and military commander. After Jan Žižka’s death, one of the foremost representatives of radical Hussitism.

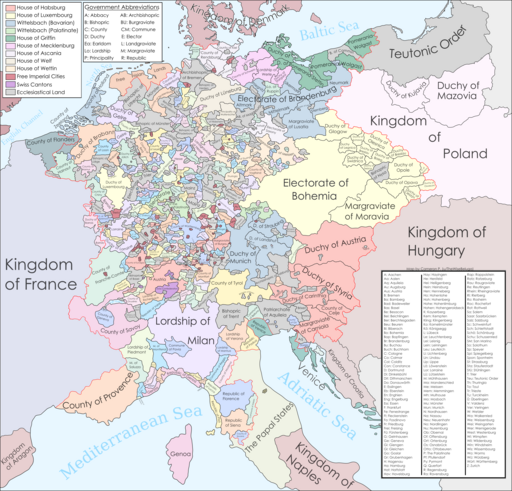

A union of feudal states in Central Europe, which for many centuries also included, at least formally, the Czech lands.

The dynasty that ruled over the Habsburg Monarchy (including the Czech lands) between 1740 and 1918 and also the last dynasty on the Czech royal throne.

Medieval preacher, theologian and teacher. He struggled for a reformation of Church and was burned for his views. His teachings are regarded as one of the first steps toward the appearance of the European Reformation.

Czechoslovak politician and eighth president of Czechoslovakia. He is called Normalisation president.

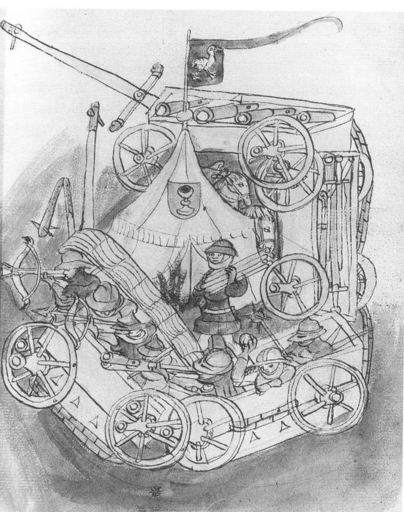

Warfare skills of the Hussites, which introduced to the Central European Medieval warfare a number of innovative elements, such as the use of war wagons, artillery and the introduction of standing professional armies.

Religious movement based on the ideas of the Czech reformer Jan Hus. Its different versions all sought to achieve a radical personal faith and equality before God. The movement also became the source of bloody religious wars at the beginning of the 15th century.

The last King of Bohemia and Hungary and Austrian Emperor. He ruled between 1916 and 1918, unsuccessfully trying to preserve the disintegrating empire during the difficult times of the First World War.

King of Bohemia between 1346 and 1378, King of the Romans between 1346 and 1355, Holy Roman Emperor between 1355 and 1378. He is regarded as the most famous Czech ruler and his reign as the “golden age” of Czech history. Shortly after his death, he was nicknamed Father of the Country.

15 September 1564, Brandýs nad Orlicí – 9 October 1636, Přerov

Charles the Elder of Zierotin was the most prominent and respectable figures from Moravian non-Catholic nobility for several decades. A purposeful and deeply religious member of the Unity of the Brethren, he was exceptionally well-educated at Protestant schools and academies in Western Europe and he stood out among the Bohemian nobility as an individual with an unusually broad European outlook. In 1591, he entered the service of King Henry of Navarre, alongside whom he wanted to fight in the war between Huguenots and Catholics. However, when Henry converted to Catholicism in order to ascend the French throne, the disappointed Moravian nobleman returned home.

On the domestic political scene, Charles the Elder was a capable politician, lawyer and diplomat who commanded respect even in his adversaries. Until as late as 1599, when he withdrew due to false accusations of high treason, he held many Moravian offices. He described the crisis of contemporary society and his disappointment with the nobility’s selfish behaviour in his work Apologia or Defence of Mister George of Hodice (Apologie, neb obrana ku panu Jiříku z Hodic), which is one of the foremost monuments of Czech humanist literature. As a long-time critic of Rudolf II, in 1607 he supported the formation of the Moravian-Austrian-Hungarian coalition, which recognised the Emperor’s brother Matthias as their ruler. With his support, he held the office of the Moravian regional governor between 1608 and 1615. Three years later, as the recognised leader of the Moravian estates he rejected Moravian participation in the Bohemian Revolt; moreover, he sought to mediate peace between the rebels and the Emperor. His attempts to keep Moravia outside the war finally isolated him and after the Brno revolution, carried out by radical Moravian Protestants in June 1619, he could only watch, from home confinement, as his country shared the tragic fate of the revolt. He is still admired and criticised for his apparently unrealistic peace efforts.

Although after the Battle of White Mountain most Protestant noblemen were either imprisoned or exiled, the Emperor did not forget the Moravian leader’s peace efforts and Charles was thus one of a few non-Catholics allowed to stay in the country and keep at least a small property. He used his influence to support and protect persecuted members of the Unity of the Brethren; e.g. he provided shelter to Jan Amos Komenský. In 1629, he went into voluntary exile to Wrocław in Silesia, although he regularly returned to Moravia, where he died seven years later.

2016-2020 ABCzech.cz - © Filozofická fakulta Univerzity Karlovy

Content from this website may be used without permission only for personal and non-commercial purposes and with the source cited. Any other use is allowed only with the authors' consent.

This web application Sonic.cgi meets GDPR requirements. Current information can be found here.